Lundazi, ZambiaJudith Mwendaendi, Head Teacher at Kanele Primary School, has seen firsthand the consequences of inadequate literacy curriculum and ineffective teaching methods. Indeed, her eldest daughter is in the fifth grade and, like many Zambian learners, has struggled with reading and writing.

Only around 65 percent of Zambians ages 15 to 24 are literate, according to UNESCO data from 2015, placing the country well behind its neighbors in the Southern African Development Community.

Outdated instructional methods and inadequate training of teachers are two of the reasons for poor learner performance. Plus, while there are seven official languages other than English in Zambia, learners have been taught in English before they could read or write in their mother tongues, resulting in poor performance in both languages.

With the 2012 introduction of the Primary Literacy Program through Read to Succeed—a U.S. Agency for International Development-funded project to support the Ministry of Education, Science, Vocational Training and Early Education (MESVTEE)—learners are making strides in literacy. The project aims to improve reading among learners in grades 1 to 4 in their local Zambian languages. It works in more than 1,200 primary schools in six provinces.

“Before the Read to Succeed project was introduced into districts, it was dismal, to say the least,” says Herbert Mwiinga, Lundazi’s District Education Board Secretary for the Ministry of Education, Science, Vocational Training and Early Education, which has taken the lead in rolling out the project. “We used to perform very badly [in literacy] as a district, but with the coming of this program, our teachers have also seen the benefits of this methodology.”

USAID/Read to Succeed uses a “whole school, whole teacher, whole learner” approach to improve learning, teaching, school management, parental and community support and responsiveness to a child’s psychosocial needs. The project is implemented by Creative Associates International.

Mwendaendi says she has seen positive results from the program among her learners at Kanele Primary School and with her own daughters, particularly her youngest, whose first grade class is participating in the phonics-based primary literacy program.

“Her beginnings have proved to us that she has gotten the concept. And for sure she’s going to be a very fluent reader by the time she will be in grade four,” she says. “It is a very good thing for our pupils, and for my daughters, specifically.”

Better teaching & management for better learning

In the classrooms of Kanele, the team of primary grade teachers Mwendaendi oversees are actively engaged with the pupils, flashing local-language letter cards as their pupils call back with the corresponding sound. As the pupils work their way through each letter sound, a word begins to emerge and faces light up with comprehension.

The new phonics-based curriculum introduced by MESVTEE and supported by USAID/Read to Succeed has transformed learning and teaching. To better get through to learners, teachers have been trained in new methods focused on phonics, phonemic awareness, fluency, vocabulary and comprehension.

“We are looking at teacher effectiveness and accountability, because we do realize that a teacher is very critical in the dispensation of education,” says Pilila Gertrude Jere, Team Leader of the USAID/Read to Succeed team in Zambia’s Eastern Province.

To date, the project has trained more than 6,200 teachers and more than 3,100 education managers in the target districts of six provinces in the effective phonics-based reading pedagogy and ways to improve a school’s reading culture, from new reading circles under trees to homegrown local-language stories written by community members, learners and teachers.

‘There is quite a lot of change in the reading culture in schools,” says Francis Sampa, Deputy Chief of Party and Teacher Development Advisor for USAID/Read to Succeed. “The reports reflect that there is a lot of activity around reading, and observations show that the children are able to read much faster than before.”

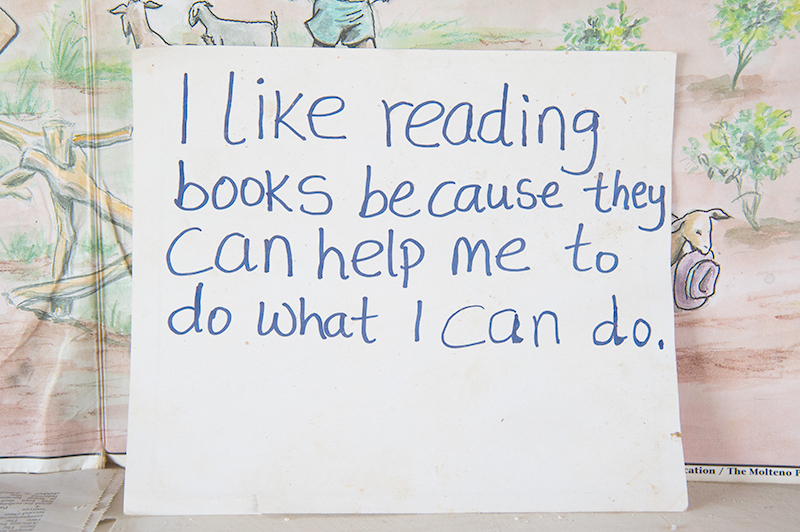

These gains in reading are due in part to that fact that pupils are surrounded by positive messages about reading, says one teacher.

“We have the writings all over the premises. The learners are able to read at whatever place they are,” says Elizabeth Zimba, a first grade teacher at Kanele. “And we have the programs where we have the learners at the reading circles where they are sharing, where they are teaching each other how to read what they’ve learned in classes.”

To ensure that teachers like Zimba have the ongoing coaching and support they need for success in the classroom, USAID/Read to Succeed has trained head teachers like Mwendaendi in education leadership and management, recognizing that the head of the school should be more than just an administrator.

“What is the role of the head?” asks Jere. “Is he supposed to be sitting in the office only to supervise, and look at that as teaching? Or, is he supposed to be an instructional leader?”

As instructional leaders, head teachers support school in-service training coordinators and hold regular teacher group meetings, where fellow teachers share ideas and discuss challenges they may be facing in the implementation of the curriculum.

Head teachers are also trained in how to conduct continuous assessments of learners and monitor teacher performance, so that struggling learners can receive additional support.

These assessments allow teachers to identify areas in which students are falling behind, says Head Teacher Rabecca Sakala at Chiginya Primary School in Lundazi. “If it’s phonics where the pupils are not doing very well, the teacher will concentrate in that. If it’s writing, then the teacher will give the pupils a lot of handwriting.”

Sakala says that since her school implemented USAID/Read to Succeed-supported interventions, the culture of reading at Chiginya Primary School has shifted and the new approach to learning, teaching and school management is paying off.

“Before Read to Succeed came into practice, the level of reading from grade one up to grade seven, it was very poor….we’ve seen that the levels of reading have gone up,” she says. “We found that a grade two pupil is able to read a storybook from maybe page one up to the last page. Even words which maybe a bigger boy can fail to read. But to find that in grade one, by the end of the year, that pupil is ready to read all the difficult words in his Zambian language!”

Community engagement spreads culture of reading

As the culture of reading is strengthened within schools and learners make strides in their mother-tongues, which they speak at home, USAID/Read to Succeed is reaching out to parents and communities to build support for literacy education after the school day ends and keep learners on course for reading success.

Across the six target provinces in Zambia, USAID/Read to Succeed schools have established 1,204 School Community Partnership Committees to engage community members in their children’s education and key decisions in school management.

“We noticed that the community itself, they feel as part of the school. They are not alienated or away from the school,” says Head Teacher Boniface Mumba at Hoya Primary School in Lundazi. “We address school challenges together with the community. And then, along with that, we see that the child feels accepted in school because we have created a school environment which is very friendly to the child.”

During school visits and committee meetings, community members are informed of school and learner progress and the implementation of school’s Learner Performance Improvement Plan, so that educators are held accountable.

Whole child approach spans beyond classroom

In many Zambian schools, learners are contending with more than just learning challenges inside the classroom—a further reason community support for learners is so critical.

HIV/AIDS afflicts roughly 12.5 percent of the population and has left more than 670,000 Zambian children orphaned, according to UNICEF data from 2012. More than 1.4 million children are orphans due to HIV/AIDS and other causes combined. In addition, many children and adolescents, particularly in rural areas, face challenges of poverty, early marriage and school dropout.

As part of its whole child approach to school effectiveness, USAID/Read to Succeed has trained Guidance and Counseling teachers on how to reach the most vulnerable learners with key psychosocial support so that they can stay on track inside and outside of school.

Community members and adolescent peer counselors, called Agents of Change, act as ambassadors of positive messages promoting healthy behaviors and encouraging learners to stay in school and parents to support learner attendance.

An eye toward future sustainability

With an eye toward the future, the MESVTEE has taken the lead at each step of USAID/Read to Succeed’s rollout—from development of the National Literacy Framework to revision of the curriculum to educator training to evaluation.

“Read to Succeed is different because it encourages and enhances locally initiated activities and innovations,” says Tassew Zewdie, Chief of Party for the project. “The project, from the beginning, has decided to work within the existing MESVTEE system, within the MESVTEE existing structure. So whatever the project does is within the existing government structure.”

The goals of the USAID/Read to Succeed, say MESVTEE officials, are one and the same as of those of the Ministry. Where the project has been critical is providing the resources and capacity building to make these goals a reality.

“It’s like Read to Succeed came in at the critical time to fit in or fill in a vacuum that was recognizable in the Ministry of Education, but due to lack of resources, we were unable to implement,” says Mwiinga, Lundazi’s District Education Board Secretary.

Mwiinga says that he and his Ministry colleagues across the district and province have participated in dialogues on exit strategy and have truly taken ownership of the program.

“It’s our program and not the USAID or Read to Succeed program,” he says. “These people have just come on board to open our eyes. And we have to carry the mantle forward on our own, with the resources that we have from government.”

The project has also built a coalition of partners, from the private sector—which has provided schools with local language reading materials—to higher education research institutions, like the University of Zambia, which have joined efforts with the MESVTEE to research literacy and develop methods to continuously improve literacy education.

This joint national effort to improve literacy education and primary grade reading levels has already proven fruitful in the Lundazi district, says Mwiinga

“At least one, two terms into this program, you have seen that actually there is some significant improvement in [learner] performance, in their reading abilities, in their writing abilities,” he says. “So to us, that’s a positive. It means the program has been accepted. It means the program is working.”