Pueblo Nuevo, HondurasRickis Mabel Gálvez Zamora told her six- and seven-year-old children that they were about to go on “an adventure.”

The young children were unaware that the family’s “adventure” would be a multi-country, irregular migration odyssey from this rural Honduras community to the United States, a journey that Gálvez Zamora had planned for two years.

“It was something very planned. I decided which things we had to take since I was going with two small children. It was not an easy decision,” Gálvez Zamora says.

Located about 30 minutes from Puerto Cortés, Pueblo Nuevo is part of a chain of rural communities situated on picturesque hills with pastures, small-plot farms and lush vegetation. Most people struggle to get by as economic opportunities never seem to reach the rural area, she says. For some residents, the economic void is filled with crime, violence and drug use. In Gálvez Zamora’s case, her bleak economic situation was compounded by violence at home.

Their departure day arrived in early August 2023. During the next three weeks, Gálvez Zamora and her two young children traveled by bus, van and car. Arriving at the U.S. border, Gálvez Zamora immediately reported herself and her children to U.S. authorities in the hope of obtaining temporary residency.

The Border Patrol “locked us up and asked for our information, but they didn’t tell us anything,” she says. “We waited and waited, and after four days, they just told us to pack our things. They didn’t tell us whether we were going to our relatives [in the United States] or going back to our country.”

The 28-year-old single mother had the answer when the Border Patrol put them on a flight back to Honduras. When the flight touched down in San Pedro Sula, the Honduran government processed the family and allowed her to call her father. A month after heading north, the family was back where they started in Pueblo Nuevo.

“You suffer a lot on the journey, there are things that leave a mark on you along the way,” she says. “Many people died along the way. We felt very sad, nostalgic and at the same time very happy because we were returning safely. Some people were crying because they had lost their spouses or their children. I was coming with my two children, so I was happy. At the same time sad because my dream was shattered.”

In debt to pay for the unsuccessful passage, traumatized by the long journey and loss of her American dream, Gálvez Zamora became depressed and closed herself in a bedroom.

Reducing irregular migration and supporting returnees

Gálvez Zamora’s story is tragic but common among the thousands of irregular migrants who are returned each year to Honduras, says Robyn Braverman, the Chief of Party of USAID’s Sembrando Esperanza activity.

A major study released this spring by USAID’s Sembrando Esperanza identified single mothers as a high risk for violence, crime and irregular migration. Like Gálvez Zamora, nearly a quarter of returned migrants are ages 25 to 29, and some 33 percent are female, according to data from the Honduran government from 2022.

Marcelo Villalvir, Sembrando Esperanza’s Senior Advisor in Migration and Youth, says the Honduran government provides basic services to returned migrants, though it is far from enough to address the emotional consequences or financial needs to re-establish themselves.

As part of USAID’s efforts to stem irregular migration from Honduras and elsewhere in Central America, Sembrando Esperanza and the nonprofit Ayuda en Acción partnered to develop a pilot program to address the financial, emotional wellbeing and rights of an overlooked and underserved population in the irregular migration ecosystem. Another goal of the effort was to reduce the likelihood that the returnees would attempt another dangerous and expensive trek.

“Sembrando Esperanza is focused on generating evidence and demonstrating that the models being implemented can create changes in people’s lives,” says Villalvir.

Vladimir Larios, Ayuda en Acción’s Director in San Pedro Sula, emphasized that the model they were developing needed to serve a broad range of returnees.

“The aim of this pilot was to test a model that could help improve the inclusive and sustainable reintegration of returned migrant populations,” said Larios during a presentation in August 2024. “Initially, we focused on research and design to identify best practices from local and international organizations working with returned migrants, addressing the significant gap in attention to this population.”

USAID’s Sembrando Esperanza and Ayuda en Acción collaborated with federal and local authorities, community organizations and international groups to build a protocol to support the social, emotional and financial needs of returnees. Though local and international organizations had the best intentions, there was little coordination among groups.

“During the design stage, many organizations would meet with us, and we had extensive conversations, very broad discussions,” Larios said. “But when it came to providing tools, learnings, systematizations or lessons learned, [the local organizations] had little to offer.”

Building a data-driven model of support

Sembrando Esperanza and Ayuda en Acción’s model leveraged the GENCAT scale, which was developed by the Catalan Institute of Assistance and Social Services in Spain to evaluate people’s psychological wellbeing by providing a comprehensive assessment across multiple dimensions of quality of life. By assessing these dimensions, a GENCAT-based “quality of life index” was developed for the pilot to identify specific areas where an individual may need support or intervention, such as emotional health, social relationships or material conditions.

When modeling and implementing the pilot, the organizations relied on experts like Ayuda en Acción psychologist Ana Gabriela Medina, who has a background in supporting people who had experienced traumatic events.

“We also conducted consultations with experts and workshops with vulnerable populations, validating our findings with returned migrants from the LGTBQI+ community, people with disabilities and violence against women and girls survivors,” said Medina, a psychologist with Ayuda en Acción, during a presentation. “This led to the development of a local assistance and reintegration protocol, focusing on planning, social and psychosocial interventions and service mapping.”

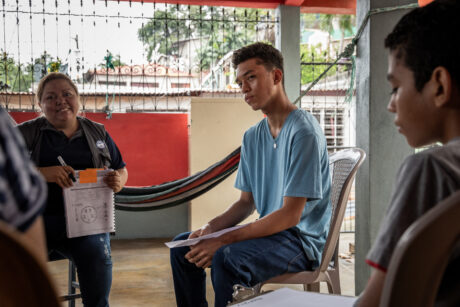

Using tools like the quality-of-life index, Sembrando Esperanza and Ayuda en Acción tailored interventions to meet individuals’ specific needs. The pilot — which provided support for six months — was implemented in Choloma, Puerto Cortés and Tegucigalpa, the areas with the largest number of returned migrants, with 105 returnees.

Medina said the psychological interventions included self-help groups with five sessions ranging from recognizing their individual migratory experience to reintegration and psycho-social therapies that included stabilization and trust-building.

In addition, the pilot developed social interventions that included strengthening safe spaces, creating life plans and developing life skills through workshops on migration rights, gender roles, health and nutrition, supported by various organizations.

Though a pilot like this was needed to help returnees integrate into their communities, Sembrando Esperanza’s Chief of Party says they faced obstacles in reaching and convincing migrants to participate.

“The challenge was not in creating the pilot. The challenge was actually finding returnees once they went back to their place of origin. This took much longer than expected,” Braverman says, noting that at times government databases were incomplete or many returnees remained in the shadows. “But once the families began the pilot, they were committed and engaged.”

Gálvez Zamora turns an emotional corner

Depressed, confused and without a path forward, Gálvez Zamora was desperate. Fortunately, a local organization recommended her as one of 30 pilot participants from the Puerto Cortes area. She was evaluated on the GENCAT scale and received individual and group therapy sessions.

“I decided to open up a bit in the first session,” Gálvez Zamora recalls. “I expressed that I couldn’t sleep, I wasn’t eating well, sometimes I would only eat once a day because I didn’t feel emotionally well.”

Psychologist Regina Ramos of Ayuda en Acción in Puerto Cortes recalls Gálvez Zamora’s critical state of mind.

“A year ago, she was at a low emotional level” based on the GENCAT scale, Ramos recalls. “The only thing that really kept her motivated was her two children. And when we started the sessions, I remember that she had absorbed so many emotions and repressed them without talking to anyone. She started crying in the first session.”

After each session, Gálvez Zamora felt a little better and slowly became optimistic that her situation would improve, a trait that rubbed off on other participants.

Today, Gálvez Zamora continues her therapy and is studying to be a mechanic, a profession often limited to men. She is excelling in her work. Her two children received school kits donated by the private sector, returned to their classrooms and are getting good grades.

Psychologist Ramos sees Gálvez Zamora as a success story.

“It’s beautiful to see the progress of a single mother,” Ramos says. “It’s motivating to see a woman move forward with her two children, a young woman who gives her best in life and decides on her own to learn to be able to thrive and start a business in this country after the migration journey. We have done a good job, not just one person but all of us together, including her and the group.”

Like Gálvez Zamora’s story, a June 2024 internal analysis of the pilot found that it provided essential and urgently needed emotional, social and financial support to returnees. Villalvir says 95 of the 105 participants had increased their scores in the quality-of-life index, with the other 10 dropping out to pursue work elsewhere in Honduras and could not continue to process.

With the success of the pilot, Braverman says it will be integrated into the municipal reception centers and run by Sembrando Esperanza and Ayuda en Acción.

“We were able to measure their wellbeing and quality of life based on eight dimensions before and after and were able to document a positive change across the eight dimensions after the intervention. Responding to the wellbeing and quality of life certainly diminishes the urge or need to migrate,” she says.

With reporting by Luis Villatoro.