Los AngelesIn his work to stem gang violence throughout Central America and in Los Angeles, Guillermo Cespedes has learned that violence and the families affected by it transcend borders.

He often tells the story of meeting a shooting victim in an L.A. hospital—an effort to interrupt the pattern of retaliatory violence—whose first phone call was to his family in El Salvador.

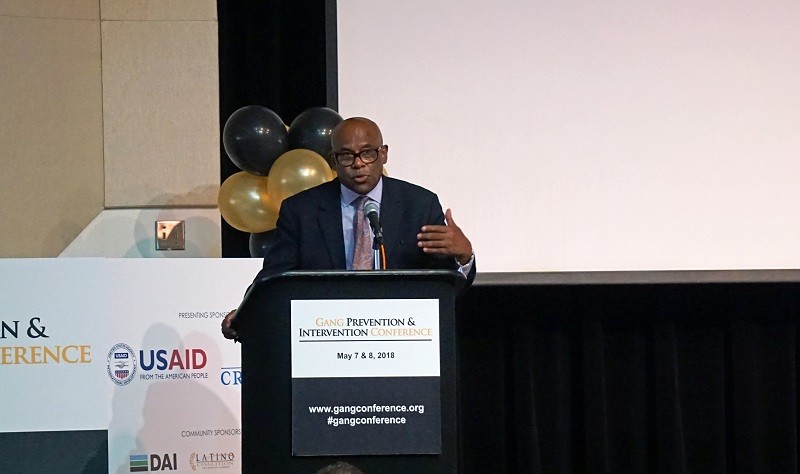

“The neighborhood is much larger than we thought,” said Cespedes, addressing an audience of 600 at the seventh annual Gang Prevention and Intervention Conference, held May 7-8. “We usually use the term ‘transnational’ to talk about crime. But in the case of Central America, there is transnational family.”

Among those gathered at the conference—former gang members turned community violence intervention workers, trauma surgeons, police officers, elected officials, civil society activists and others—some 150 attendees came from outside of the United States.

Cespedes, formerly Deputy Mayor of Los Angeles and director of its Gang Reduction and Youth Development office, said the international presence at the conference – increasing every year – parallels the growing sense in the field that what happens in the United States and in Central America is interconnected.

Currently a Senior Advisor on Crime and Violence Prevention with Creative Associates International, Cespedes has also served as Deputy Chief of Party for the USAID-funded and Creative-implemented Proponte Más project in Honduras, which uses a family counseling model to reduce youth risk for violence.

In this position and his career in Los Angeles, he has worked with many families with members on both sides of the border.

He said that while families and the challenges they face spread across international borders, the solutions to violence must be adapted to each context.

“I think any medicine that gets exported to Central America actually comes back stronger,” he said. “But I don’t think it’s possible to take even what’s most effective in L.A. and just suddenly transfer it to Central America. I think there’s a process of adaptation that needs to take place. That adaptation takes really knowing both sides, both contexts.”

Allowing communities to lead

Speaking on a plenary panel alongside Cespedes, Rosita Amaya of Catholic Relief Services in El Salvador stressed the importance of engaging communities in peacebuilding based on their specific needs and hopes.

“We need to ask the people who are working on the ground first to see what’s working and create a collective strategy,” she said. “My dream for the future is that we are able to include the people that can actually give us the answer to those problems.”

Cespedes added that effective violence prevention work not only adapts to the local context, but also recognizes that not every person within that location should be treated in the same way, or administered the same “medicine.”

“What’s needed is the right level of intervention for different types of populations,” he said. “Not all the people in a particular neighborhood have their fingers on the trigger. We do have to address those with fingers on the trigger differently than those who are maybe thinking of getting a gun.”

Throughout the conference, speakers and attendees highlighted the need for a holistic approach that weaves together violence prevention, intervention or interruption and law enforcement.

Strategies outlined included visiting shooting victims in the hospital to offer them an exit ramp and prevent retaliatory violence; reclaiming public parks as no-violence zones with free programming; and building collaboration between outreach and law enforcement.

Balance between enforcement and prevention

David Kennedy, director of the National Network for Safe Communities at John Jay College, said one root cause of cycles of violence is the deterioration of government legitimacy and trust between communities and the state.

“Serious violence is concentrated in very small populations of exceptional folks. They are at astronomical risk, they live in communities that have been subjected historically to terrible oppression and damage and are not getting the type of attention and support that they need,” he said. “If you do not trust the police and someone is trying to attack you, you are not going to ask for help, you are going to take care of it yourself.”

Considering this pattern, strengthening positive ties between the communities and law enforcement is a critical step to stemming violence, panelists said.

In his remarks at the conference, Los Angeles Police Department Chief Charlie Beck underscored the need for law enforcement to work hand in hand with community outreach efforts to improve relationships between neighborhoods and police that have often been shattered, such as during the city’s war on drugs and gangs that led to thousands of arrests.

“When you declare war on a significant piece of the population, you declare war on yourself,” he said. “The most important thing a department and community can have is trust.”

With a change in law enforcement’s approach, Beck reported that gang crime has been cut in half over the last 10 years and that 2018 is on track to set a new low in homicide rate and number of shooting victims.

“This is done by hundreds of people working very hard to change the way our community sees itself,” he said.

Same principles, new lens

While the core pillars of violence prevention – a public health approach pairing appropriate interventions with levels of risk, holistic programming, partnerships, data and sustainability – remained at the heart of the conference, many speakers called for a continued effort to think critically and take on the problems from a new angle.

“At this field evolves, the lens is going to develop, it’s going to be refined more,” said Fernando Rejon, Executive Director of the Urban Peace Institute. “We’re going to learn more when we look at things from different perspectives.”

For some, like Catholic Relief Services’ Amaya and Creative’s Cespedes, this means flipping the script on evidence and focusing not just on what communities’ lack or struggle with, but where they draw strength from. In the case of the USAID-funded Proponte Más project, that has meant expanding the view of youth risk factors for engaging with gangs and violence to also look at protective factors, such as feeling safe in school.

“It’s looking at data through both lenses, not just what’s wrong but what’s right,” said Cespedes. “We have to not just be capable of moving the camera around and finding a different angle, we have to be able to take the lens off the camera.”