As salas de aula das escolas primárias na região sudeste de Mtwara, na Tanzânia, e nas ilhas de Pemba e Unguja, em Zanzibar, são mais barulhentas do que costumavam ser, mas os alunos estão aprendendo mais e aprendendo melhor. Usando ferramentas inovadoras e métodos de ensino envolventes, educadores recém-formados estão redefinindo a aparência da aprendizagem, e sons, gosto e, no processo, transformando crianças mais bem educadas.

“I hear head teachers telling us about the noises that are coming from classes. To me that’s called an educational buzz because children are learning and those are active learning environments,” diz Renuka Pillay, who leads the Tanzania 21st Century Basic Education Project, also called TZ21.

The project is improving primary education for children in 900 primary schools in the Mtwara region and Zanzibar’s Pemba and Unguja islands by empowering educators to teach reading, math and science more effectively. Working with Tanzania’s Ministry of Education and Vocational Training, os EUA. Agency for International Development-funded program bolsters professional development for teachers through mentoring, peer-to-peer support, teacher learning circles and better training. É implementado pela Creative Associates International.

An education crisis emerges

In a drive to achieve higher rates of primary school enrollment, Tanzania’s Ministry of Education and Vocational Training began offering free primary education in 2002. The surge in enrollment that followed—jumping from only 59 percent of primary-school-aged students enrolled in 2000 para 96 por cento em 2010 no continente e quase 80 percent on Zanzibar—overwhelmed a teacher population already struggling to teach critical thinking and foundational science, math and reading skills.

Although Tanzania was filling more classrooms with students eager to learn and seemingly on its way to achieving universal primary education, the quality of instruction lagged behind. Teachers talked, imparting information, e estudantes, for the most part, sat on benches and listened.

But student performance indicated that little learning was actually occurring. Em um 2013 study by Uwezo, um grupo da sociedade civil da África Oriental que monitoriza o desempenho educativo, apenas 53 percent of Tanzanian students over 10 years old could pass a Kiswahili literacy exam, com apenas 35 percent passing a literacy test in English.

Mtwara, a target region of the program, was one of the most hard-pressed regions in need of an educational reboot.

“Mtwara is one of the underserved regions in the country with very poor infrastructure and overcrowded classrooms,”diz Félix Mbogella, deputy chief of party of the project in Mtwara. “We have teachers who have never attended a refresher course or any kind of trainings to sharpen their teaching skills for over 20 years.”

Giving teachers the tools for success

Em 27 Teacher Resource Centers in Mtwara and 10 Teacher Centers in Zanzibar, including one national resource center based on the island, primary school teachers receive support from peers and trainers to improve their teaching methods and subject matter knowledge. Mais do que 1,200 teachers in Mtwara and 490 in Zanzibar have been trained as mentors and coaches to date.

The centers’ hands-on training, mentoring and coaching programs focus on techniques that incorporate student engagement and integrate early grade Kiswahili reading across the curriculum in grades one through four.

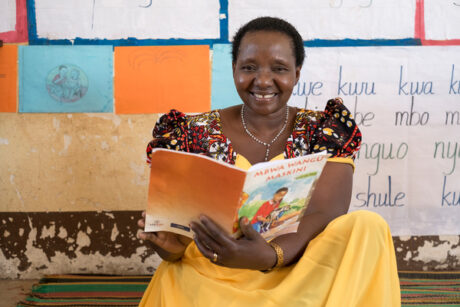

With previous teaching methods, “teaching was very difficult,” says Blandina Lucas Ndambalilo, a Teaching Resource Center Coordinator in Mitengo in the Mtwara region. Teachers “just used a single technique…and couldn’t identify problems with individual students.”

Using these new approaches, which prioritize and track student progress, Ndambalilo says “the teacher can see what students are missing and where to fill in. We’re now taught to avoid spoon-feeding.”

Coordinators for the Tanzania 21st Century Basic Education Program observe teachers in action in the classroom to identify gaps and needs in their teaching methods followed by one-on-one discussions with the teachers. This collaborative and individualized approach leads to tailored and effective support for instructors. Um grupo de instrutores mestres – professores e funcionários escolares que foram treinados como treinadores – fornecem orientação contínua a colegas educadores.

Nos Centros de Recursos para Professores e Centros de Professores, professores do ensino primário aprendem a gerir eficazmente salas de aula repletas de alunos com processos e necessidades de aprendizagem únicos. Os instrutores fornecem aos educadores ferramentas práticas para a sala de aula, incluindo a incorporação de tecnologia e o ensino da alfabetização em Kiswahili por meio da fonética.

Capacitado com essas novas abordagens, os professores estão renovando criativamente suas atividades em sala de aula e percebendo uma diferença qualitativa em seu trabalho.

“Antigamente era normal entrar numa sala de aula sem as ferramentas necessárias para apoiar o ensino,” diz Mektidis Nguli, a grade one teacher at the Mangowela School in Mtwara. “But now I have access to so many tools….I have so much at my disposal to support my teaching, and teaching therefore is just an enjoyable activity, as opposed to how it was before.”

Witnessing a learning transformation

Teachers are not the only ones feeling a positive change in the school environment. Inside the classrooms, the flurry of student activity displays a much different scene than the one teachers describe before the training program, when tools were limited and knowledge was delivered in a one-way stream from teacher to student.

“Kids now are gathering in groups, playing games in groups, discussing, reading to each other, writing books, singing—in a way that inspires reading,”diz Mbogella.

With students more excited by their lessons and more engaged with their teachers, peers and the material, Tanzania is well-positioned to sustain its high rates of primary school enrollment and maximize learning outcomes for its youngest students.

Ali Saher Ali, a parent of a student in a Tanzania 21st Century Basic Education Program school sees this transformation on a personal level. “As a result of this [programa] I can mention that the teachers, they are doing splendid work which should be congratulated, because I can see that result in my son.”