[vc_row][largura da coluna_vc=”1/1″][vc_column_text]

Histórias de imigrantes: Dual identity

Por Jennifer Brookland

[/vc_column_text][/vc_coluna][/vc_row][vc_row][largura da coluna_vc=”2/3″][vc_column_text]

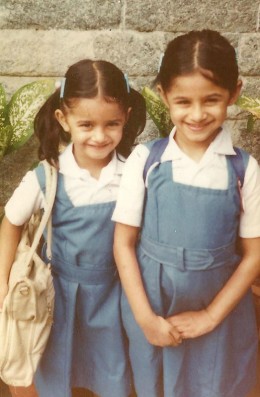

Anitha Pai remembers the day in third grade when all the kids in her Edmond, Oklahoma, classroom brought in their baby photos to guess who was who. Her classmates struggled to identify which blonde toddler was which blonde classmate. Only one photo showed someone different: a little girl in a bright Indian outfit and a red bindi dot on her head.

It wasn’t the only time Anitha, who moved from the UK to India and finally at age six to the United States, was reminded that she was different from her classmates. Todos os anos, her mother was asked to return to the school to explain Indian culture.

“Nobody else’s mom came to class!” says Anitha. "Bem, except for the Jewish kid’s mom. Every year it was the one Hindu mom and the one Jewish mom.”

For an organization like Creative Associates International—which continues to attract talented immigrants to its Washington, DC, headquarters and field operations around the world—hearing their stories helps us honor their contributions and reflect on our common drive to explore and succeed.

Many immigrants who come to the United States at a young age struggle to combine their family’s heritage, religion and culture with the desire to fit in amongst American peers.

That struggle wasn’t always easy for Anitha in Edmond, Oklahoma.

Although Anitha only lived in India for a year and a half—sandwiched between her early years in the UK and her family’s departure for the states when she was six—she considered herself Indian. Her name had been selected by her paternal grandmother in keeping with tradition. Her family spoke Konkani at home. Anitha remembers leafing through the bound volume that traces her family tree deep into India’s past.

Although she only lived a short time in Chennai, Índia, she easily remembers the home where every room was painted a different color. The green room, the blue room, the yellow room and—the favorite of her and her sister—the pink room, where Anitha would stand proudly and recite her multiplication tables as her parents nodded their heads in encouragement.

Although she only lived a short time in Chennai, Índia, she easily remembers the home where every room was painted a different color. The green room, the blue room, the yellow room and—the favorite of her and her sister—the pink room, where Anitha would stand proudly and recite her multiplication tables as her parents nodded their heads in encouragement.

Her time in an Indian school was a different matter, where teachers would smack children with rulers for not knowing the answers.

“I exaggerate a little when I say it was traumatic,” says Anitha, “but it was really hard.”

The harsh teachers and rote memorization of an Indian classroom came as a shock to her, after spending her preschool years in a British Montessori-style school.

“I think the relationship I had with my teachers and the understanding I had of their role in education was something that shaped me a lot at a young age,”ela diz.

Her time in Indian classrooms was short lived. All along, her family knew they were going to immigrate to the United States. It was, to them, the beacon of freedom of choice that beckons so many others who arrive seeking a better future for their children.

“In India, if you’re smart you go into medicine or engineering,” says Anitha. “Those paths are dictated for you.”

Her parents wanted to give their children the chance to choose their own futures. And so, when Anitha was six years old, they all boarded a plane bound for the U.S. for good.

Anitha moved with her parents, siblings and grandparents to Edmond, Oklahoma, where the cost of living was low and the traffic even less. Edmond had a population of around 53,000 when the Pai family moved there. Chennai, then called Madras, tive 10 times that.

When she started school, Anitha began confronting cultural challenges immediately. It was the little things that she had to figure out quickly and on her own—like how to act in the school cafeteria.

“Nobody sits down and explains that to you. My parents didn’t know,”ela diz. “But we would notice how people stand in line [to be served lunch] and we would just pick up these norms.”

For her parents and grandparents, it took a bit more effort to assimilate into American culture. Felizmente, a strong Indian community welcomed the family and provided a connection to the place they had given up.

After a while, Anitha grew to consider herself to be an American. She became a naturalized U.S. citizen along with her family. Even though citizenship had been the plan all along, it still felt meaningful.

“Para nós, it was this idea of making it: to be in a country where you have these options and these opportunities,”ela diz. “It felt like we fit in.”

But it wasn’t until Anitha returned to India that she realized how fully acculturated into the United States she had become.

The family had visited in the years since they had emigrated, usually spending a month in the summers visiting relatives. But Anitha decided that she wanted to return and work in India after she graduated from college. She wanted to know the country she had left, and—with her growing interest in international development—see how its people really lived.

She thought her parents would be thrilled.

“I thought my parents would be so excited because I would advance professionally and personally,” says Anitha. “My dad was shocked by this idea. It took me some time to realize why he was so shocked. Os EUA. was his home now. He didn’t really think about my interests in discovering this place that I didn’t really know.”

De fato, being so rooted in the United States gave Anitha the confidence and interest to return to India. When she arrived in Bangalore on her own, people immediately knew she was from somewhere else.

“I could put on an Indian outfit and I wouldn’t say anything and they could just figure out that I wasn’t Indian,” she remembers.

A far cry from her Oklahoma elementary school, Anitha saw people who looked like her everywhere in Bangalore. And yet it was obvious she was no longer entirely Indian. In India, she was American.

A far cry from her Oklahoma elementary school, Anitha saw people who looked like her everywhere in Bangalore. And yet it was obvious she was no longer entirely Indian. In India, she was American.

That sense of foreignness helped Anitha in her fieldwork, as she traveled around the country meeting with people and helping set up a financial literacy program for a microfinance institution. People were willing to talk to her, and share deeply. She planned to stay in Bangalore for 12 months but ended up staying for two years.

“It was one of the best decisions I’ve ever made,”ela diz.

Now a program associate in Creative’s Education Division, Anitha loves getting the chance to help empower youth who oftentimes, in cultures like India’s, are disenfranchised and told their voices are not important.

She thinks of all the choices she’s been able to make as a young adult that were only possible because she lives in a culture like America’s, which builds young people up and gives them the chance to take risks and make their own decisions.

On a recent trip to Yemen, when people repeatedly referred to her as Indian, she would correct them, saying that her parents were from India and she is American.

“Having this dual identity is key to who I am,” Anitha says. "Agora, I’ve come to a point where they meld together. Growing up it was a struggle. Agora, it’s comfortable.”

Her experiences have helped her feel an instant bond with other immigrants working at Creative.

“When you meet someone from an immigrant family, you know certain challenges and ways of thinking because of that experience,” Anitha says. “I have immigrant friends from all different cultures. There’s a common thread there.”

It also gave her a special connection with the communities that Creative works with.

“It’s pretty common with immigrants to give back, because we’ve received so much,”ela diz. “You have this obligation to give something more.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_coluna][largura da coluna_vc=”1/12″][/vc_coluna][largura da coluna_vc=”1/4″][vc_widget_sidebar barra lateral_id=”barra lateral primária”][/vc_coluna][/vc_row]