Zanzíbar, TanzaniaAt the turn of the millennium, las cosas estaban mal para los estudiantes tanzanos. El apoyo entusiasta a la educación primaria y la alfabetización que surgió con la independencia se había visto mitigado por el hambre., sequía y crisis económica que desviaron dinero de las escuelas. Las tasas netas de inscripción disminuyeron a apenas 57 por ciento en 2000.

Y luego, a comeback. With government programs and policies like the abolishment of primary school fees, coupled with foreign aid in furtherance of the Millennium Development Goals, Tanzania’s education sector was on a major rebound.

Kids were doing better on tests, textbooks and math kits arrived in crates and boxes, teachers were recruited and sent to live where perhaps they would have just as soon avoided. Funcionó. Por 2007, the UN reported Tanzania’s net primary school enrollment had just about doubled.

But it was one of the worst things that could have happened.

The high enrollment rates nationwide now mask a major problem. With so many kids in falling-apart schools, with few books and fewer teachers, the fact that students go to class does not mean they are learning.

En 2013, solo 5 por ciento de los alumnos de primer grado de Tanzania podrían aprobar un examen de suajili, de acuerdo a a report by Uwezo, un grupo de la sociedad civil de África Oriental que monitorea los logros educativos. Despite their diligent attendance and best hopes, low-quality education is setting these kids up for failure: the same report reveals only 35 percent of Tanzanian children aged 10 a 16 can pass a literacy test in English—the language of instruction in secondary school.

“It’s very, very painful if your kid went to school for seven years consecutively and, leave aside all other kinds of knowledge, he or she cannot read and write," dice Félix Mbogella, the deputy chief of the Tanzania 21calle Programa de Educación Básica del Siglo, also known as TZ21, a program that works to improve learning outcomes in Tanzanian primary schools.

el programa, financiado por los EE.UU.. Agency for International Development and implemented almost exclusively by Tanzanian employees of Creative Associates International, operates in 900 schools in Zanzibar and the Mtwara region.

Winning against illiteracy on multiple fronts

While the Tanzania 21calle Century Basic Education Program cannot reduce class sizes, Mbogella lists the ways the project chips away at the abysmal performance of too many young students. It’s taking a “whole school approach”—improving learning outcomes by addressing students, profesores, schools and even communities.

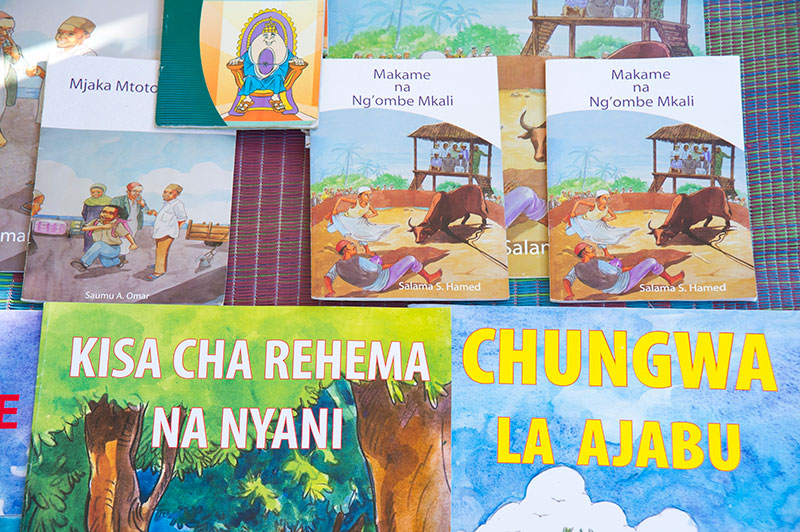

The program has refurbished schools, partnered with a local children’s book publisher to get more grade-level storybooks into classrooms and trained school management committees on how to support development activities like building latrines or organizing reading fairs.

It connected the schools with the world by bringing in computers and incorporating e-content into lessons—changing the way school had been taught for decades, maybe centuries.

“Our classrooms were classical African classrooms," dice Mbogella. “Benches, kids and teacher, blackboard and chalk. And now that has changed. Our classrooms are very engaging. You find lots of pictures, words, alphabets, games…”

One of Mbogella’s favorite ways to describe how school here used to be is “chalk and talk.” There was no singing, no moving around, no group work, no games. It was the classroom of his childhood and one he doesn’t remember particularly fondly.

With a major focus on teachers, la tanzania 21calle Century Basic Education Program worked to make the classroom environment completely different from the school rooms of last century’s Tanzania.

It showed teachers how to really engage students by changing up activities, moving around the classroom, breaking them up into groups and soliciting their creative input for crafting teaching aids.

“There is an empowerment of teachers to be creative educationists, not just to manage kids and shoe them and leave them quiet," dice Renuka Pillay, the program’s Chief of Party, describing the sounds and scenes of children actively participating in learning activities in their classes.

To directly impact literacy, the program also familiarized teachers with a five-step approach to teaching reading that they can attest is working.

The approach leads children through phonics, conciencia fonémica, vocabulary, reading comprehension and fluency—importantly: in that order.

“I am very thankful to the project for upgrading our skills with such a holistic approach,” says teaching coach and mentor Cyrprian Ali Ndaka. “Now we are very comfortable with the five reading components and they’re being followed sequentially- and the impact is vividly clear.”

Bringing lessons to life

At Kisiwandui Primary School in Zanzibar, a projector and a white sheet draped over a blackboard are enough to transform what Mbogella would have decried as “chalk and talk” into a lesson kids are excited about.

The teacher walks around the rows of desks with a sisal bag, collecting imaginary food items from each row of uniformed pupils. She is going to Machuri farm, ella dice. What should she bring? Forty or so second graders throw imaginary items into her bag, smiling as she weaves among them.

Now a little girl with a white head covering walks the basket around to gather gifts from her classmates- apples and cucumbers. Songs and clapping punctuate the lesson, hands wave in the air. The teacher stands with her arm draped over the student as a video developed by the program plays on the makeshift screen. It shows students in a classroom just like this one playing the same game.

Soon the words they’ve contributed will be used in a phonics lesson. The teacher starts grouping words that start with the same sound: Ua– flour. Uzi– thread. Ubani– incense.

“We were using energy—so much energy—to [enseñar] things without involving students,” explains Blandina Lucas Ndambalilo, a Teacher Resource Coordinator in Mitengo. With Tanzania 21calle Programa de Educación Básica del Siglo, ella dice, “Teachers learned how to use the students’ energy and what’s in their own minds. It’s a participatory method. It used to be the teacher was the one giving knowledge to the students. But now it’s the students giving knowledge and the teacher guides them.”

Halima Usi Haji, who teaches second grade at Kisiwandui Primary School, says with the new teaching methods and e-content, children have become more attentive, more curious, and better able to follow the lesson.

Teachers at other schools go even further: they say the new approaches have reduced absenteeism and even dropout.

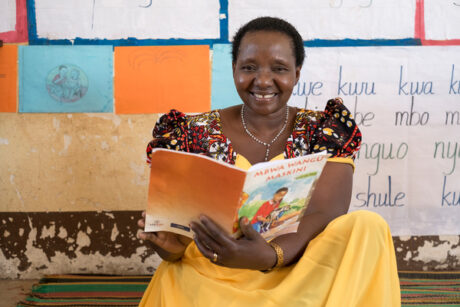

“If you had seen the schools before and you [saw] the schools now they are quite different,” says Pilli Dumea, the executive secretary of the Children’s Book Project. “There is tremendous, tremendous change. Positive change. The classrooms have become more attractive. They have become lively through the use of electronic devices…There are library corners in the class, which were not there before. So now when you go to those classrooms you know there’s something happening here.”

Learning that lasts

Dumea says children are motivated to learn by the changes they see in their schools. They have increased their interest in reading, también: School librarians in both Zanzibar and Mtwara reported more students are coming to borrow books.

In the past three months, 400 students at Kisiwandui have checked out books, according to librarian Jane Hebron Lazaro. TZ21 also trained librarians on how to manage libraries and track which titles were out—helping schools identify which books to buy.

At Chaume Primary School in rural Mtwara, librarian Tatu Shabani Dalhi says children used to check out between 10 y 12 books each week. Ahora, she registers 40 un dia.

By improving students’ ability to read, it’s clear that their interest in reading is growing as well—a virtuous cycle that TZ21 has encouraged schools to sustain by continuing to support teachers and engage community members.

Mbogella says between April and October of 2013, literacy rates among participants went up 13 por ciento.

The evidence is preliminary, but it speaks to the success of looking beyond the numbers of kids in school and taking a hard look at what those kids need—across the curriculum, in the whole school and outside of it—to truly learn.

“Just imagine," dice Mbogella. “You have this national challenge where our kids cannot read and write for seven years consecutively. And if you have managed to come up as a team, as partners…with this powerful tool. We have come up with this powerful dose, where for the first time just in five months our kids can decode; our kids can read and write. So that motivates us. That really, really motivates us.”