Significant resources and efforts have been dedicated to addressing state fragility around the world for many years. However, on the Fragile States Index rankings, the number of countries that scored 90 or above – at the threshold for alert, high alert or very high alert – has remained consistent since the start of data collection in 2005.

This is in spite of considerable progress toward improving infrastructure, education and health, as well as reducing global poverty in the same time period.

Experts have increasingly recognized that traditional approaches to development are not sufficient to address state fragility.

In a new publication series, “Reframing Fragility and Resilience,” Pauline H. Baker, Ph.D.—a leading expert on fragility—provides fresh insight into the relationship between fragility and resilience, and the way forward for dealing with fragile states. The report was commissioned by Creative Associates International as part of its Governance and Community Resilience Practice Area.

As explained in her publication, “resilience” exists when a society has the capacity to not only return to status quo after a shock, but also to transform itself into a stronger state than it was previously.

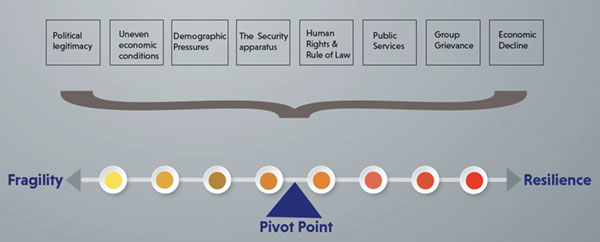

Baker proposes that fragility and resilience exist in a continuum, with a state’s place on this continuum determined by a series of factors, such as demographic pressures, human rights and rule of law and economic inequity (see figure 1).

Movement along the fragility/resilience continuum is not linear or unidirectional. Some states experience a swift, violent collapse, such as Syria, while others deteriorate more gradually, such as Venezuela. Some states may see resilience grow in some areas while backsliding in others, and many persist in a “fragile equilibrium” as brittle states for decades.

With very few exceptions, no state is entirely fragile or entirely resilient.

In Libya many municipalities continue to function peacefully in spite of state collapse and the outbreak of war, while prosperous liberal democracies, such as the Netherlands and France, continue to contend with group grievances around national identity, race and religion that periodically produce violence.

Risks for instability

Within the fragility/resilience continuum, the report’s author identifies some key risks for fragility and commonalities among fragile states. The three most significant factors in fragility are illegitimate government, growing group grievances and macroeconomic decline. In combination, these factors increase the risk of conflict and instability.

Many fragile states are also characterized by tight-knit power structures, termed “Limited Access Orders,” in which networks of elites – including politicians, the military, business leaders and bureaucrats – hold a monopoly on resources. Examples of Limited Access Orders can be found around the world, in countries as diverse as North Korea or Zimbabwe.

This type of governance system has a direct link to the other factors influencing fragility: Limited Access Orders contribute to structural and persistent poverty, competition over resources is intense, and groups without opportunities to access wealth or power feel marginalized and aggrieved, and these all erode the government’s legitimacy.

The transformative path forward

The fragility/resilience framework illuminates how and why most traditional approaches to addressing state fragility have fallen short. These traditional approaches have focused on improving service delivery, building the capacity of state employees and strengthening civil society—and they have aimed primarily at reducing fragility rather than fostering resilience.

For a state to become resilient – that is, to improve, not simply to survive – it must transform its governance system and take a holistic approach which builds on existing resiliencies and addresses points of fragility.

Effective approaches to addressing fragility should:

- Support a shift from a Limited Access Order to an Open Access Order, which provides more opportunities to more citizens, encourages social mobility and increases inclusion, which will in turn help to reduce group grievances and improve legitimacy.

- Identify resiliencies on which to build interventions and leverage local assets. For example, if one city in a fragile state is functioning well, the program could try to replicate those best practices nationally.

- Pay particular attention to legitimacy, both the political legitimacy of state actors as a key factor in resilience and fragility, and also the legitimacy of the intervention.

- Develop nuanced, multifaceted interventions to address the complex factors at play in the fragility/resilience continuum. Approaches should be highly contextualized to the local environment as possible, and should be based on detailed, current information of citizen perceptions.

It is simpler for a state to become fragile than it is for a state to build resilience. Baker’s research, for example, found while fragility often results from declines in three factors – political legitimacy, group grievance, and macroeconomic growth – the path to resilience relies on a combination of those three factors plus decreased demographic pressure, improved public services, reduced inequality, and respect for human rights and the rule of law.

It is simpler to focus on service delivery or capacity building, or to respond to immediate humanitarian crises, than to attempt a fundamental transformation of a governance system. But without attention to the structural conditions that create fragility no efforts to strengthen a fragile state will be sustainable or successful in the long term.

By reframing these approaches and placing a focus on resilience, the fragility/resilience continuum provides a new paradigm for addressing state fragility.

Maggie Proctor is a Technical Manager in the Governance and Community Resilience Practice Area at Creative Associates International.