When Nigeria’s schools closed in March due to COVID-19, teachers and students — like many around the world — left their classrooms unsure of when they would be able to return.

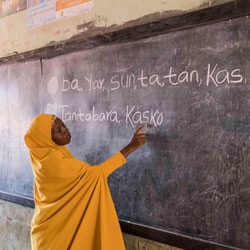

The USAID Northern Education Initiative Plus program (NEI Plus) — which has worked to strengthen access and quality of basic education through new and engaging teaching approaches and learning materials, teacher training, nonformal learning centers and more — was faced with the challenge of protecting the progress and learning gained over five years as students faced an indefinite time out of school.

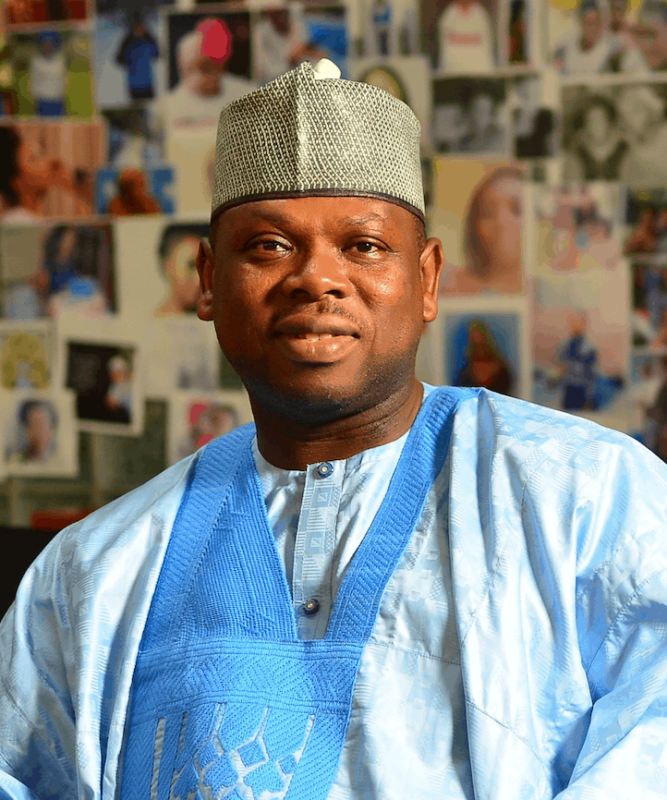

In this Q&A, NEI Plus Chief of Party Nurudeen Lawal breaks down how the program responded to the pandemic and the lessons learned over the past several months.

At the onset of the pandemic, how did the NEI Plus team respond?

Nurudeen Lawal: You know, you dive into something and you don’t even know how big it is. But we had a very good start, because immediately we understood that of course we are in a pandemic, and the best thing to do is to ensure that people are safe.

So, the first thing that we did even before we had the first case in Nigeria was to organize awareness sessions for staff about it and give regular updates. And we ensured that this information was cascaded down to our beneficiaries through SMS and WhatsApp.

Not long after we had the first case in Nigeria, we decided to close the non-formal learning centers that we operate with local civil society organizations at the end of March. We have 1,600 non-formal learning centers with about 50 learners each, so we suspended activities and sent the students home with homework. The government closed the public schools as well, and then we closed our offices and commenced working from home.

We developed a contingency plan with activities that we call pivot activities that helped to mitigate the pandemic and at the same time made sure that project activities continued. These were targeted at making sure that learners continued to learn from home and that the beneficiaries get sufficient messages on how to protect themselves from the effects of the pandemic. We did this with a vigorous communication strategy through social media, through SMS and through WhatsApp in English and Hausa. We also supported the state governments in helping them look at their own contingency plans to see how well it responds to remote learning and prevention from the pandemic.

We also started looking into strategies of radio programming, TV programming, IVR (interactive voice response) lessons and how we can continue our activities in terms of helping community structures such as women’s groups and community coalitions to be able to pass on messages of prevention and mitigation of the pandemic.

As a matter of fact, at the very onset of the pandemic, a video was made of children washing their hands, and that video went viral and was used by our partner project in the Northeast, was televised and sent around on WhatsApp and social media.

I can say that in the height of the pandemic we are able to also continue a major activity: the development of new materials in Igbo and Yoruba for early grade readers in primary grades 1, 2 and 3. Working virtually, we were able to develop a large number of texts stories and vocabularies in both languages. This was a great achievement for us during that period.

How did the project use media to keep students and teachers engaged while they were out of school?

Nurudeen Lawal: Importantly, reducing learning loss was addressed through regular use of the radio and TV programs. We developed materials for remote learning, which are all based on the teaching and learning materials that we use in classrooms, called Let’s Read! in English and Mu Karanta! in Hausa. We developed scripts for radio, TV and IVR based on these existing materials. The IVR messages run for six to seven minutes. They were sent to parents and teachers and reached more than 11,000 people within the first few months. We also infused social emotional learning and COVID-19 prevention tips and information.

We also kept the teachers engaged in continuous professional development through SMS and WhatsApp so that when they resume school, they will be ready and they wouldn’t have themselves lost what they know.

I also want to add that at the federal level, there were resources available online. The federal Ministry of Education opened several online portals for learners.

How is the project helping students get back to classes safely?

Nurudeen Lawal: We developed a checklist for resuming the non-formal learning centers that includes, for example, how students are organized. We used to have 50 students at a time, and now they are divided into three clusters to keep class sizes down. We’ve also provided handwashing stations.

In addition, we created a school reopening framework document and we supported the governments in observing schools resuming in Bauchi and Sokoto states and were able to give them feedback on what we have observed. We were able to hold meetings with them to share the framework and ensure they focus on not just prevention of the pandemic from spreading but also how to gain back the lost learning time that the children have experienced.

Looking back on the past several months, what are some of the lessons learned?

Nurudeen Lawal: There are lots of lessons learned around remote learning during this period. And for me that is something for future research: What are the gaps that we saw in trying to run remote learning during a pandemic? What resources were not available? One thing was that of course we had not trained teachers to be able to develop or support remote learning activities. So, it was quite challenging. Teachers became emergency radio teachers and TV teachers, and everything was deployed in response to the situation. But I think we responded to the situation perfectly. We had the minds of the learners engaged during that period and understood that they can learn from home and should not spend the whole time playing. We were also able to provide them social emotional learning activities that kept them mindful and that helped their general psychological wellbeing.

I think that one of the greatest lessons learned is also that from now on, when we plan to have remote learning content and face-to-face content, making blended learning standard for education activities moving forward.

I also think that in terms of learning, we need to support governments in ensuring that they have in place remote learning framework. We need to understand that when we program, we need to program in parental support for learning. This could bridge a big gap in remote learning programs. The project depended on community outreach materials, whereby parents were engaged to really support their children. The radio program and the other blended approaches could be much more successful if parental support for learning is further emphasized. We need to come up with approaches whereby parents can to some extent provide enabling environment in terms of discussing with the child what they have learned, playing games or doing activities together, providing radios at home for the kids or making a phone available for instructional messages to the kids.

Another lesson is how much we can actually achieve working online. We see that we can engage our local partners online to the extent possible. We also saw how much we can achieve working from home. We were able to do so much, and I see that as the way to go in the future.