This blog was first published on the Market Systems Development Hub as part of the 2020 Market Systems Symposium. Creative is a sponsor of the symposium, which is organized by EcoVentures International.

As it interrupts supply chains and halts transport, the COVID-19 pandemic is exposing weaknesses in the resilience of market systems across the globe. This is true for the Nigerian maize market, which lays bare the need to strengthen market systems for post-pandemic recovery.

On March 30, the Nigerian government instituted a lockdown of the capital of Abuja and Lagos and Ogun states to contain the spread of new COVID-19 cases, and several other states also opted for various levels of lockdown. The restrictions on mobility and trade placed immense pressure on the country’s domestic production, which had already seen increased demand and prices due to the government’s reduction of imported cereals.

The pandemic also coincided with the crop planting period, contributing to the rise in input and maize costs by roughly 40 percent, according to the Nigerian Agricultural Policy Project. The immediate rise in key staple prices, which has implications for this season’s harvest and foreseeable impacts on GDP and poverty in Nigeria, highlight the maize market system’s lack of resilience to shocks.

Market systems resilience and proactivity

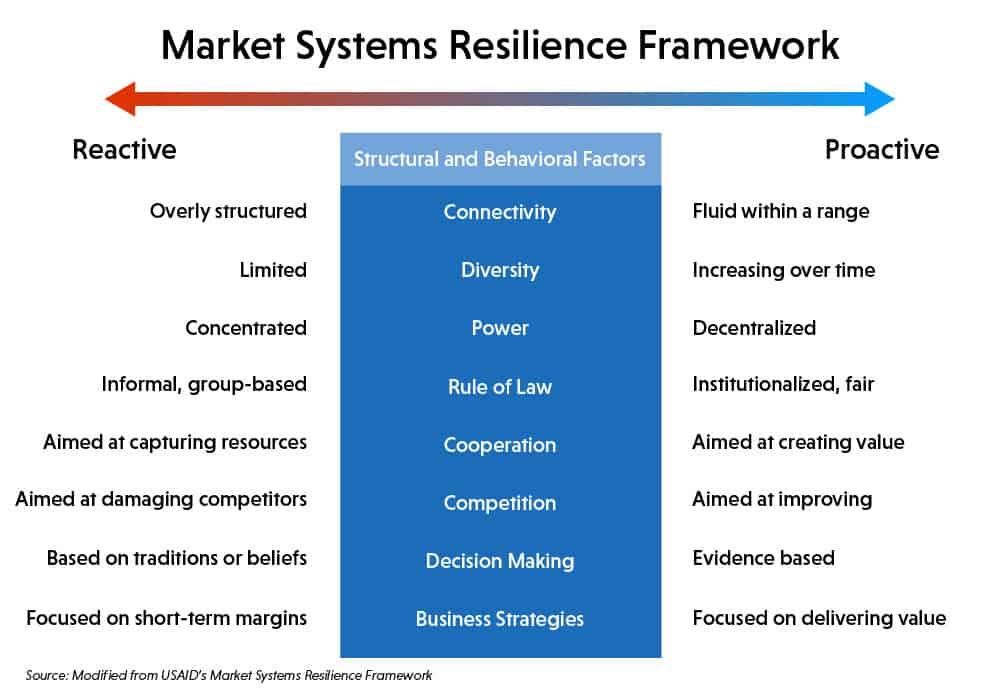

Market systems research and development interventions in the past few decades have attempted to unpack and address ways to bolster livelihood outcomes. The Market Systems Resilience framework released by USAID’s Bureau of Food Security in late 2018 went a step further to explore structural and behavioral characteristics of how markets do or don’t transform to shocks, including unforeseen events such as COVID-19.

The authors argue that markets range from reactive (inhibitive) to proactive (enabling) in their ability to absorb, adapt or transform in the face of shocks and stresses. They also make a distinction between fast-moving (e.g. prices and supply) and slow-moving (system-level) variables and point out that most development interventions focus on the fast-moving variables directly impacted by a shock like COVID-19.

However, there is a need to find ways to address slow-moving variables, such as market structure and gender norms, that can transform market systems in the long run.

A look at the Nigerian maize market

In 2018, the Nigeria Agriculture Policy Project undertook a survey of 1,400 maize traders to understand the structure of the maize value chain. They found that the rural-urban maize supply chain in Nigeria can be visualized as a massive hourglass, with tens of millions of small farmers growing maize, 100 million people buying maize and 10,000 urban maize traders and a well-developed third-party logistics services and warehouse rental market that guide market trends. The study found that farmers not participating in outgrower schemes receive practically no advances from traders at the onset of the planting season, thus most of the risk is concentrated with smallholder growers at the top of the hourglass.

In recent years, the Nigerian government has tried to rectify some of the issues in the maize market, in which power is concentrated in the hands of traders, informal rules prevail, there’s limited diversity and competition, and short-term margins drive decision making. These factors set the maize market up to be reactive — which is why it was hard hit by COVID-19.

Shortened market hours and restrictions on transit between states during the pandemic shutdown had a direct impact on various components of the maize value chain, including the production of poultry and fish feed. In rural areas, input costs for maize farmers increased. Poultry producers faced shortfalls due to logistics constraints. A range of actors such as food stall retailers, small shops, rural and urban wholesalers, trucking businesses, logistics firms and warehouse companies were widely impacted. This led to a substantial drop in income for those who depend on these industries for their livelihoods, not to mention inflation of food prices for a wide swath of Nigerians.

Addressing slow-moving variables

Given the example of the Nigeria maize value chain and other similar cases throughout the Global South, how can development actors impact slow-moving variables to make market systems more resilient and advance toward more proactive behavior?

This is a question that Creative hopes to address in the West Africa Trade and Investment Hub. In collaboration with USAID and private sector agribusinesses, the project has redirected a portion of USAID’s $60 million co-investment fund to bolster the local food supply and ensure that businesses working with smallholder farmers help them access key inputs and pre-financing, given the impacts of COVID-19 on farmer income, supply chains and other constraints. This contributes to building a proactive market system that is adaptable to future risk by developing new business models, norms and incentives among market actors.

We will be looking to enhance market behaviors that decentralize power of traders, potentially through technology and enhanced farmer networks, improved competition, and increased access to data that allows farmers and consumers to make better decisions. Most importantly, our ability to directly co-invest with innovating U.S. and Nigerian agribusinesses to adapt their business models in the maize, soy, rice, cowpea and aquaculture value chains, deliver value for customers and suppliers, and challenge gender norms within their own operations and broader supply chains will help make these market systems more resilient to shocks from future crises like COVID-19.