[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

How the story of a greedy dog engages children in rural Zambia to read

By Jillian Slutzker

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”2/3″][vc_column_text]

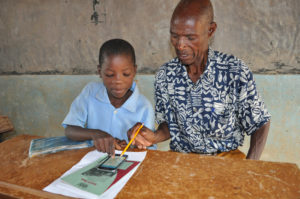

Chipata, Zambia—Adamson Thawete dropped out of school after the ninth grade to work as a miner. But he proudly boasts that all nine of his children have completed twelth grade, at his insistence. He beams when he rattles off their professions—a hotel manager, a teacher and a banker, among others.

Now it falls on him to ensure that his grandson, 10-year-old Lico Yamba, a third grader at Nyana Primary School, gets an education. Equally important, he wants to be sure that Lico learns to read and write in their local language, Chinyanja, and ultimately in English.

“I took a keen interest in educating my children…for them to lead a better life. An educated person fits well into a civilized community,” says Thawete.

While Thawete is committed to his grandson’s education, in their rural Mang’awa village he doesn’t have all the resources he needs, namely books.

Like most schools in the province, Nyana Primary School faces a shortage of local language storybooks. While the Ministry of General Education transitioned to teaching local language in primary schools in 2014, there are very few publishers of local language books and they cannot keep up with the growing demand as young readers advance and the need for these books multiplies. Household poverty and a lack of Ministry resources have also prevented local language books from reaching students.

At home, many new readers have nothing to read.

Fortunately, Lico Yamba’s community is taking part in Makhalidwe Athu— a mobile reading project using SMS messaging to bring crowdsourced, local language tales to Zambian children and families. Lico Yamba’s family is one of forty families with second and third grade students at the Nyana Primary School taking part in the pilot.

The project is implemented by Creative Associates International. It is funded through All Children Reading: A Grand Challenge for Development, a partnership of the U.S. Agency for International Development, World Vision, and the Australian Government.

Gathered together over a mobile phone, Thawete guides his grandson who reads word by word through a short story in Chinyanja. The story is written for second grade level reading skills, calibrated to the scope and sequence of the second grade level reading program.

This scene will play out weekly in 1,200 households associated with 40 pilot communities across Eastern Province as short local language stories are delivered, in three segments, via SMS messaging directly to the mobile phones of families.

To aid comprehension, each story is followed by a series of questions parents ask their children. The questions are asked through SMS and interactive voice response, and a recorded version of the story is available to assist illiterate parents. Answers to the questions are written in Makhalidwe Athu exercise books provided by the project.

As each story segment comes in, children write them down in exercise books provided by the project, so that by the end of the 2016 pilot year they will have a treasure trove of 52 stories to revisit again and again.

These stories will also serve as a resource to non-pilot school communities and families, explains Margaret Phiri, Chipata District Resource Center Coordinator for the Ministry of General Education, an instrumental partner in the project.

In a cardboard box, Phiri keeps printed versions of the mobile stories on small cards that are available for any educator in the district to use in his or her classroom.

She wants to ensure “that every teacher and parent becomes part of it.”

“The excitement is there for the project,” she adds. “They don’t need to walk very far. At their homes they will receive the stories. It makes them excited and get motivated.”

Mobilizing parents & community

Parents and community members are pivotal in making Makhalidwe Athu a success, explains Bridget Chilala, a Community Mobilizer for the project in the Lundazi District.

Chilala and her co-mobilizer, Martha Musopelo, hold monthly community meetings at the local primary schools where they orient and educate parents on their important roles and responsibilities—covering topics from the mechanics of receiving an SMS message and copying it down and deleting it to make room for the next one to the process of coaching children through the stories and allowing them to take the lead.

While mobile phones can be found even in the most rural villages of Eastern Province, mobile technology as a tool for education, especially outside the classroom and at home, is a new concept and requires some orientation, explains Chilala.

Mobile phones “are an added benefit to reading. They have used paper for a long time, but now using their phones becomes dynamic. It’s a plus for this community,” she says, adding that parents also gain technology skills in the process that can help them in other ways.

Phiri, the District Resource Center Coordinator for Chipata, says that in many cases, neighbors are gathering to share the stories with those who may not have access to a phone.

“It’s bringing unity in the community,” she says.

In his village, Adamson Thawete is calling on his neighbors to support the project.

“I would like to urge my fellow parents to support and assist our children to attaining education for the betterment of our communities…Makhalidwe Athu is there to support and uplift our education standards,” he says.

In addition to their role as mobilizers and facilitators of their children’s reading of the mobile stories, many community members are also contributing stories themselves, which are crowdsourced through SMS, interactive voice response, the project website or submitted in paper to Breeze FM, a local radio station partner. A team of project staff and Ministry of General Education officials then edits the story, ensuring it is targeted to grade two level reading skills, and adapts it for the SMS format.

As parents, authors, and advocates for the initiative among their neighbors, it is the community that really owns the project, says Chilala.

“When they are partners, they feel honored and when they feel honored, the program will take.”

Local tales resonant & teach

The tales dispatched through the project are culturally relevant and locally grown, crowdsourced from community members and 16 local writers trained as project authors.

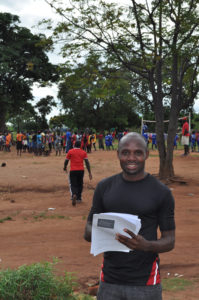

Island Daka, a Chipata primary school teacher, is one of these authors trained to write short, simple, culturally relevant and grade appropriate stories for the project.

One of his favorite works is a tale featuring a greedy dog who falls in a pond while trying to steal the bone from the dog he sees in the water (i.e. his own reflection).

These are characters and stories the children can understand, says Daka.

“If you write a story that is culturally relevant to them, they get more interested and excited in the story,” he says.

Other tales communicate lessons about health, farming and food and preventing early marriages, among the top causes of school dropout among adolescent girls in the area.

“We feel these stories should depict what happens in the local community…where children can learn these lessons,” says Abigail Nyirenda, District Resource Center Coordinator for Lundazi.

Daka is confident that locally produced stories like these will help to create strong readers and flourishing communities.

“I think in the near future there are going to be more people literate…and if more people are educated the community will develop,” he says.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/12″][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”sidebar-primary”][list_category_posts_widget title=”RELATED STORIES:” cat_id=”119,255″ order_by=”date” numberposts=”3″ excerpt=”yes” excerpt_size=”15″][/vc_column][/vc_row]